The Discursive

Construction of “Women” in Las Américas:

An Analysis of

Sixteenth-Century Print Culture

There is a lack of consensus on

what terms are best to use when speaking historically about the racialization

of Indigenous peoples in the Americas, particularly in light of the long career

of pan-American terms: Indian, American Indian, Native American, Red,

Aboriginal, First Nation, Indigenous, Amerindians, or any of their counterparts

in Spanish, French and Portuguese, (etc.), languages. Each emerged in a specific context and each has a particular

meaning associated with it, so it’s very difficult to use one of them at all

times in all contexts. As a result

a term may be more accurate or relevant depending on what’s being discussed,

but for the purposes of this dossier I will use “Amerindian” to emphasize the

artificial, discursive construction of people in the Americas as one homogenous

group. I’ll use “Amerindian”

to help lessen the confusion around the more historically accurate term

“Indian,” as that term was also used to describe people from India and even

Africa in the early sixteenth-century.

When I use “Indigenous,” it

is to signal the critical interventions people have made in claiming a

pan-Americas identity as a political strategy.

Also, when I use terms like “the

New World,” or “Europe” they’re always meant in scare quotes so as to destabilize

the way these terms have become naturalized as if true. It is important to remember, for

example, that these lands were only “new” to some people, certainly not the

people who lived here, and not even to those who had crossed the Atlantic

before 1492.

This article is, on a

broad level, about language, meaning and how we interpret the world we live in.

It is to understand how language

and actions come together to produce and define the objects of our knowledge

(such as Anthropological understandings of the human), and the exercise of

power in categorizing certain persons as particular 'types.’ But more

specifically, it is an analysis of early sixteenth-century representations of

women in the Americas, and how they were used to form the misguided understanding

of ontological, stratified, differences between “Europeans”, “Amerindians,”

“Africans” and “Asians.”

A central premise of this article

is that meaning is relational.

What this means in this context, is that narratives regarding “Amerindians” were constituted in relation with

other narratives, not only ones about “Europeans”, but also about “Africans”

and “East Indians.”

Let us be clear that this is a

moment in history where the idea of continents did not yet exist in the way

they do now. There was an ongoing

debate about land and water masses between different classical theories, but

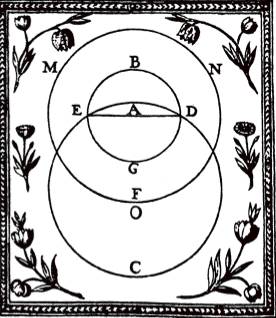

none specified the continental scheme we now often take for granted.[1] There were a variety of world maps at

the time, but the one you see below seems to have had a special role in the

early rejection of Christopher Columbus’s proposal to sail across the Atlantic.[2] It was a time when “Europe” was on the

economic periphery of Muslim Kingdoms and Chinese Empires.[3] In fact, it was only the wealth reaped

from the colonization of the Americas and the Atlantic slave trade that

facilitated Europe’s ascension in the global economy.

Engraving of the spheres of the earth and the water before

and after the congregatio acquae on

the Third Day of Creation, according to

Paul de Burgos who was influenced by Aristotle, Additiones (written in 1429), in Nicolai de Lyra,Postillae

Nicolai de Lyra super totam Bibliam cum additionabus, Nuremberg, 1481.

What is the

relationship between individual perceptions, such as those held by Spanish

colonists about the gender and sexuality of the peoples they encountered in the

Americas and Africa, and a representational system of contemporary

stereotypes? How did the notions

about “cannibals”, “Amazons” and sexual licentiousness that were so prevalent

at the time become an integrated part of European cultural perspectives of the

“new world”?

It so happens that the

book, as it emerged as a collection of bound papers mechanically reproduced

with words printed in ink, shares a historical temporality with

colonization. When

Portuguese explorers were embarking on the first voyages to southern Africa in

the early 1440’s, Johann Gutenberg, a German goldsmith, among others were

busily working to perfect the reproduction of printed matter by mechanical

means.[4]

The first book to be

mechanically reproduced, the famous Gutenberg Bible, was published in

1452, eleven years

after the first voyage by Antam Gonćalves to Western Africa with the direct

purpose of engaging in a slave raid.[5] News from

returning slave raiders, and the imaginations it sparked made for fascinating

storytelling. The print machine

would facilitate both the production of Eurocentric imaginings of the Americas,

Africa and the Orient, feeding colonists with myths of monsters and cannibals

where there were none, but also be used to print the religious texts needed for

converting the peoples of the Americas to Christianity.[6]

The emergence of the book and the

publication of popular texts such as the one focused on in this article, Paesi

Nouamente Retrovati, thus aided I argue, in the creation of an imagined community of

“civilized, light-skinned, sexually chaste, Christians” long before the

nationalisms of later centuries that Benedict Anderson discusses in his book Imagined

Communities.[7]