Sexuality, Gender and the

Colonial Encounter: Constructing the Amerindian

Colonialism did not impose

pre-colonial, European gender arrangements on the colonized. It imposed a new

gender system… It introduced many genders and gender itself as a colonial concept

and mode of organization of relations of production, property relations,

cosmologies and ways of knowing.[1]

María Lugones

Columbus

himself wrote another letter that appears in Paesi, and it became one of the most

famous records from the early colonial period. In it Columbus describes the people of the Americas both in

contrast to, and in relation with Africans and uses highly sexualized and

gendered language. He compares

Amerindian people to the people of Guinea in West Africa distinguished only by

their straight hair. Columbus also

describes the people he encounters as cowardly, innocent, keenly intelligent,

cannibalistic and sexually deviant.

Columbus writes:

They are no more malformed than

the others, except that they have the custom of wearing their hair long

already mentioned, and arm and

protect themselves with plates of copper, of which they have much.[3]

This

allusion to an island inhabited by Amazon women is important. The Amazons of Greek myth, believed to

live in Africa and Asia, are described in those myths as “a people who excelled

at war…and if they ever had intercourse with men and gave birth to children,

they only raised the girls.”[4] They were also known for going to war

and killing many Greeks. Amazons

are further described as living in ends-of-the-earth locations. Such a description implicitly connotes

an external and subordinate position in the Greco imaginary, for it was

believed that the farther one was from the Mediterranean “heartland” the more

degenerate one’s culture was.[5] In Greek society only men went to war,

and so “Amazons symbolize what in the polis is a normative masculinity.”[6]

Their

placement at the edge of the known world “is a spatial expression of their reversal

of patriarchal culture: Amazons blur the categories that classify the domains

of male and female.”[7] They further represent a “structural

reversal of the paradigm of civilization and the organization of power.”[8] In other words, at the edges of the

known world, in this case what was believed to be the peripheral islands off

the coast of mainland China, the binaries of human/divine, human/animal, or

male/female are being reinterpreted in unique form. It is here that Columbus is locating what would become known

as the Caribbean. A close

examination of the discovery letters in Paesi, uniquely organized in an edited

volume, demonstrates the historical specificity of discursive gender formations

across geo-political divides.

Referencing

a universal patriarchy and/or a universal male/female difference to understand

the history of gendered discourse in racialized communities does not

suffice. Rather we need to examine

the unique way that masculinity and femininity were specifically constituted in

and between Europeans, Amerindians, Africans and Asians.

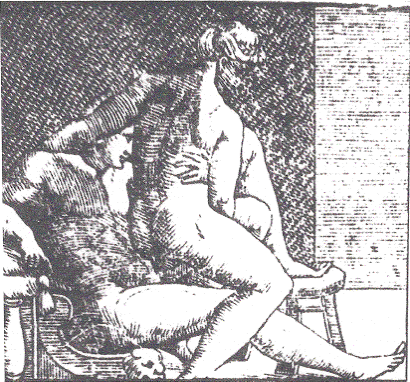

To do so,

it is helpful to consider early print erotica, as it is yet another genre that

was emerging vis-ą-vis the mechanical reproduction of the book. For example what is widely considered

the first book in the history of pornography, I Modi translated as “The Positions” by

Marcantonio Raimondi and Pietro Aretino, was printed in 1527.

Anonymous 16th Century Artist, I Modi, Position 10, Woodcut after Marcantonio Raimondi after Guilio Romano. In former Toscanini volume.

Private Collection, Geneva.

Early

erotic representations of European women, such as those found in I Modi, were a matter of judgment and

moral outrage, understood as a threat against the basic purity of “good women.”

[9]

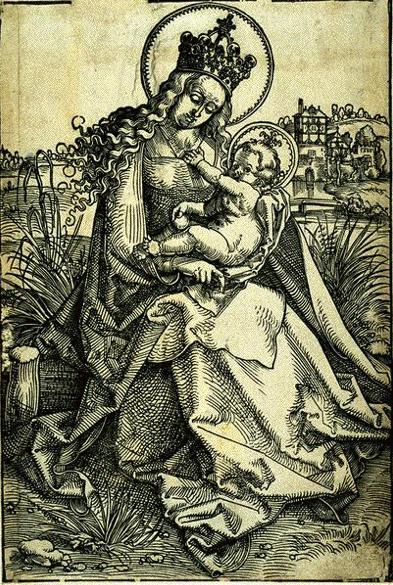

Indeed,

the array of available images, from the religious to the erotic, created an

extremely limited repertoire of imagery about Euro-Christian women; the chaste

and the unchaste. However narrow,

the possibility of being a “good woman” was in fact present for western

European women, whereas in these foundational depictions of the Americas, being

a “good Indian woman” was not in the repertoire of possibilities.[10]

Hans Baldung Grier, Madonna and Child on a Grassy Bench. Woodcut c.1505-07.

The University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor.

The

imagined hypersexuality of women in the Americas was not attributed to the

behavior of a few, but rather, was written as constitutive of who they were as

a people. Furthermore, the

outrageous sexual romps and consumption of human flesh in the images about the

Americas was not perceived by Church authorities as an excess of Christian male sexuality, as in the case of

European erotica,[11]

but rather as truth-building depictions of a society in which women were

primary sexual aggressors.

Early

colonial print culture’s imaginary regarding women in the Americas as those who

perform the sexual roles normally attributed to European Christian men, at once

masculinized Amerindian women and effeminized Amerindian men, encapsulating the

people of the Americas as a gender role-reversed people specific to a

geographic location.

Simultaneously, the narratives implicitly demarcate heterosexuality

proper as the purview of those in God’s company: that is Christian Europeans.

Another

important aspect of these tales of Amazons and sexually licentious men and

women in the Americas were not only interpreted as a sign of human inferiority,

but also conversely, as narratives of a freer society. Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Redicker

state in The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary

Atlantic that

these reports about the Americas, “inflamed the collective imagination of

Europe, inspiring endless discussion—among statesmen, philosophers, and

writers, as well as the dispossessed.”[12] In addition to the idea that in the

Americas lived a people without property, work, masters, or kings, also lived

the idea that a people were more sexually liberated there. For some, these discovery narratives

invoked dreams of utopia.

In Imperial

Leather (1995),

Anne McClintock further argues that the “[K]nowledge of the unknown world was

mapped as a metaphysics of gender violence—not as the expanded

recognition of cultural difference—and was validated by the new

Enlightenment logic of private property and possessive individualism.”[13] To further

McClintock’s point; gender itself, even in Europe, was under a significant

shift in the sixteenth-century. In

the wake of social unrest left by the decimation of populations effected by the

Black Plague (During the fourteenth-century about 30% - 40% of the “European”

population was wiped out), political authorities began deploying sexuality in

particular ways. For example, the

decriminalization of rape against peasant women became the social norm.[14] In the sixteenth-century, witch-hunts

were used to destroy the power of European women and to foster deep divisions

along gendered lines within the working class.[15] Land expropriation, enclosures and the

exploitation of peasants significantly rose during this period, beginning the

long process of relegating to the home European women’s contributions to

community life.[16] In other words, European colonists’

deployment of sexuality and gendered discourse to define people in the Americas

was also being deployed in their European communities, albeit in a distinct

manner.

It is in

this context we can better understand the meaning and implications of

representing people in the Americas as gender deviant. Whether it was believed that people in

the Americas were utopian or cursed, both narratives could be interpreted as a

threat to the organization of power in sixteenth century Western Europe. Early woodcut images of the Americas

allow us to see the moment in which the mechanically produced image of the body

is posed as one of sexual difference, and writ large on the collectivity called

“the Amerindian” that has the potential to literally consume the European male

body: penis, limbs, torso and head included.