Printing “las Américas”

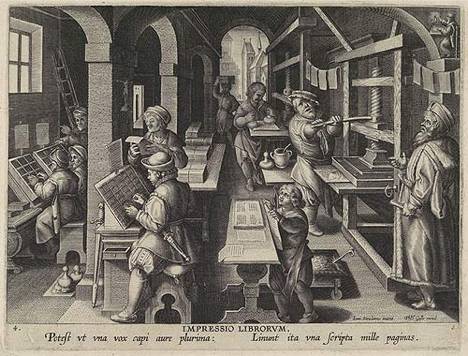

Impressio Librorum [Book Printing]: Plate 4 of the Nova Reperta [New Discoveries] by Theodor Galle (Flemish, 1571 - 1633) after Jan van der Straet (Netherlands, 1523 - 1605). Antwerp: Philips Galle, late 16th Century.

These texts and

images, originally written and drawn by individuals, were then transferred into

typeface and woodcut blocks, printed, and circulated widely. The printing press facilitated the

process of integrating these texts and images into a system of

representation. In fact this was

one of the key impacts the printing press had on the production and

circulation of knowledge in western and northern Europe. Images, maps and diagrams could be

mechanically reproduced in quantities larger then previously seen, and at a

speed faster than ever possible, creating the opportunity of an “exactly

repeatable pictorial statement.”[1]

In the groundbreaking

book, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, Elizabeth Eisenstein

argues that typography arrested linguistic drift, meaning, that the print

machine helped enrich as well as standardize vernaculars, and paved the way for

the more deliberate purification and codification of all major European

languages. Eisenstein discusses

these themes as they relate to shifts in labor dynamics, and religious and

scientific revolutions.

However almost nothing

is said in her book about how the print machine impacted the Americas. It was against this precise backdrop of

standardization, purification, codification and nationalization in European

book production that, for example, Hernan Cortez was ordering the destruction of Indigenous Nahuatl

books and records. In fact in 1573

the Spanish Crown went so far as to illegalize any written reference to Indigenous

ways of knowing. An edict was

issued stating, “Under no consideration should any person whatsoever write

things touching on the superstitions and manner of life which these Indians

formerly had.”[2] So the

unrestrained proliferation of books such as Paesi Nouamente Retrovati that distributed

these stereotypical narratives of Amazons and cannibals in the Americas, was

paralleled by the prohibition of reproducing books detailing Indigenous

epistemologies, particularly those written by Indigenous peoples themselves.

The effect of an

“exactly repeatable pictorial statement” that only represented the Americas in

highly problematic ways was that it standardized and reproduced words and

images about people in the Americas, manipulating the lens through which a subject

could be understood, even delimiting what aspects could be thought about. This phenomenon coupled with the

dissemination of the printed book to a scattered array of readers helps explain

the conditions for producing stereotypes.

As new editions and

translations of books regarding the Americas were printed, there remained a

steadfast representation of the people as (for example) lawless cannibals and

societies of Amazons. These

reproductions were a key aspect of the material conditions for producing a

stereotypical notion of people in the Americas.

To put this in a global

context: Just as printing favored

the growth of the Reformation, so it helped mould modern European

languages. During the 16th

century, there took place a process of unification and consolidation that

established fairly large territories wherein a single language was written.[3] The contemporary development of the

idea of a “territorial language” which would later transform into the “national

language,” as they exist today, was happening at the same time and in response

to the encounter with southern Africa, the Americas and India. While modern European languages were

defining themselves into heterogeneous, autonomous entities there was also the

simultaneous process of defining the people of the Americas as homogenous,

abnormally gendered and subordinate to Europeans generally. Arguably, the dissolution of a common

Latin culture was replaced by the affirmations of local difference in Rome,

Italy, Germany, France, Spain, and Britain, all consolidated by the printing

press. [4] Yet this shift didn’t signal the total

collapse of a sense of a shared location in the world. What we see, instead, is the rise of an

implicitly gendered notion of “the European” taking firm hold.

The monies that were flowing into

the countries of Spain and France from the new colonies were facilitating the

centralization of “national” monarchies, and publishers wanting to ever expand

their markets, encouraged the standardization of languages over a large area so

as to be able to sell their products as easily and cheaply to as wide an

audience as possible.[5]

All this was occurring in the context of cross-Atlantic expansion, a growing

African and Amerindian slave trade and the establishment of new colonies where

literacy was regulated to only perpetuate European systems of power.[6]

The gendered discourse in books

regarding Indigenous peoples of the Americas would have a lasting negative

impact and would be key to the solidification of a particular notion of European

masculinity. What we commonly

refer to today as differences of race, gender and economy must be recognized

not as entirely separate categories that intersect only occasionally, but

rather as always already intertwined categorizations across difference with a

shared history in the colonization of the Americas and the expansion of the

Atlantic Slave trade.

By way of conclusion, the link

between the representations of Amerindian, African, Asian and European people

as mutually constitutive, which I have sought to elucidate herein, has been

largely neglected in cultural studies scholarship. Its sexual dynamic, specifically the representation of

Indigenous people as Amazons, cannibals and lascivious women as so clearly

illustrated in early woodcuts and books such as Paesi Nouamente Retrovati

(1507), were

constitutive in the emergence of ideas surrounding the Americas, and in the

emergence of race itself as a dominant organizing principle of social and

economic relations. Examining the

key role of sexuality in the early representation of “the Americas” exposes it

as playing a key role in justifying and even naturalizing trans-Atlantic

violence. In so doing, it brings

forth the possibility of asking new or more nuanced questions with regards to

gender, particularly as it is constructed in racialized contexts.