5.12 Trees, Birds, & Bees

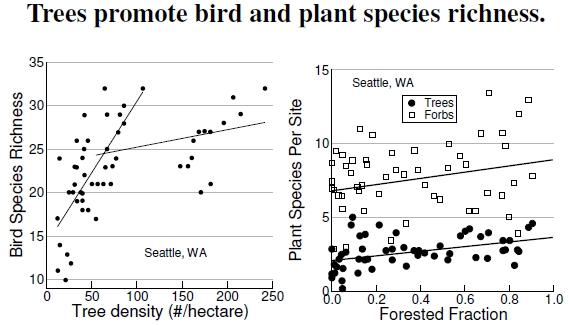

Figure 5.12: At left, censusing birds in developed areas of Seattle, Washington, demonstrate increasing species richness with tree density (after Donnelly and Marzluff 2006). In that area, if you want birds, you need a minimum of 10 trees per hectare. At right, another look at Seattle connected plant species surveys with measures of forested areas in 1 square kilometer parcels, finding that areas with a greater fraction of forest cover have significantly more tree and forb species (after Hansen et al. 2005). Shrub species, however, didn’t increase significantly with forested fraction.

Nature also values nature. The previous set of plots showed that people simply enjoy seeing a diversity of birds and trees, and the graphs shown here in Figure 5.12 demonstrate, at least in urban Seattle,Washington, how bird and plant species richness depends on tree and forest abundance.[48] At left, the two different spans of tree density indicate that, at low tree density, every 6 trees per hectare (about 2.5 acres) adds another bird species. At higher densities, above 50 to 100 trees per hectare, every 50-some trees adds a new bird species.[49] Lots of trees also beget lots of plant species, here again shown for Seattle. Tree species diversity increases with forest cover, as well as the forbs, which essentially constitute all herbaceous flowering plants, excluding grasses.

If you value birds and want them in the city, then residential lots need an absolute minimum of 10 trees per hectare, or about 5 trees per acre, with about one-quarter of these trees being evergreens.[50] In other words, if you have a onequarter acre lot (about 100 feet by 100 feet), then you should have at least one evergreen and one deciduous tree. Better yet, have five of each. Of course, birds don’t care about the boundaries of city lots, so having a couple of trees on a one-quarter acre lot in the midst of a treeless subdivision of manicured lawns won’t do much for the birds. Promoting high urban bird populations becomes a community endeavor, a public good, something that should done by homeowners for the greater good of nature, as well as a public health benefit via insect control (see Figure 5.2).

Keep in mind that not every square meter should be turned into tree canopy: Some bird species require early successional grassland environments (also vastly different from a manicured, pesticide-covered lawn). As evidence, increasing urbanization in Boulder, Colorado, reduced the richness of bird species preferring grasslands,[51] and many bird species went from present to absent when urban landcover fractions exceeded a value around 50%. In such a situation, cities—at least cities that want birds — should be kept below 52% urban landcover, with some forest patches of at least 42 hectares in extent.

As far as patches go, wildlife need multiple reserves that serve as sources and sinks for colonization and extinctions.[52] Whether or not parks and treed neighborhoods, along with stream corridors, serve as multiple reserves, no one really knows. Until scientists better understand such practical urban ecology concepts, just make the guess that more reserves are better than fewer reserves.

—————————-

[48]Donnelly and Marzluff (2006) performed an extensive study of bird species richness in Seattle, Washington, and recommend having at least 10 trees per hectare in cities. Hansen et al. (2005) reviewed many aspects of urban sprawl on biodiversity and reported the plant species diversity effects of forest cover.

[49]My piecewise fits to the Donnelly and Marzluff (2006) data may be questionable; indeed the original authors didn’t do it, and their statistical analyses may be preferred over my approach. However, the large gap in the middle of tree density causes practical interpretational challenges. For my analysis, the fit for low tree density gives R2 = 0.49 and and a fit y = 14.1+0.164x. The fit at higher density is almost significant (p = 0.067) with a fit y = 23.2 + 0.020x.

[50]Birds like to roost in evergreens. I remember once searching for a missing chicken one night, and being startled when parting the branches of a backyard cedar tree, I found a sleeping cardinal.

[51]Haire et al. (2000) examined grassland bird species in Boulder, Colorado, and found decreasing richness with urbanization. They also make recommendations on urban land cover.

[52]McCarthy et al. (2006) discuss sources and sinks for colonization and extinctions.