Using a text editor and regular expressions¶

What is a text editor?¶

Unlike a word processor, a text editor only handles plain text (i.e. no graphics or fancy formating). However, in return, text editors provide powerful tools for manipulating text, including the ability to use regular expressions, highlight differences between two or more files, and search and replace functionality on steroids. Since most data is available in or can be exported to plain text, and computer programs are written in plian text, a text editor is one of the most basic and useful applcations for anyone dealing with massive amounts of data. Text is universal - unlike binary formats (try to open a WordPerfect 4.2 document), text documents are editable on any platform, and will still be readable in 30 years time.

First look¶

This session will asume that you are using the TextWrangler editor on a Mac. The functionality of most text editors is very similar, and you should be able to follow along if you are using a different editor. We will take the lazy option of familiarizing you to TextWrangler by using the official tutorial. Open TextWrangler and take a few minutes to familiarize yourself with its anatomy - look at the menus, toolbars, icons etc. Most of this should be pretty familiar to you from other programs. Open the file Lorem ipsum.txt in the Tutorial Examples/Lesson 3 folder. Now read the description of the toolbar on Page 10 of the tutorial.

Mini-exercise¶

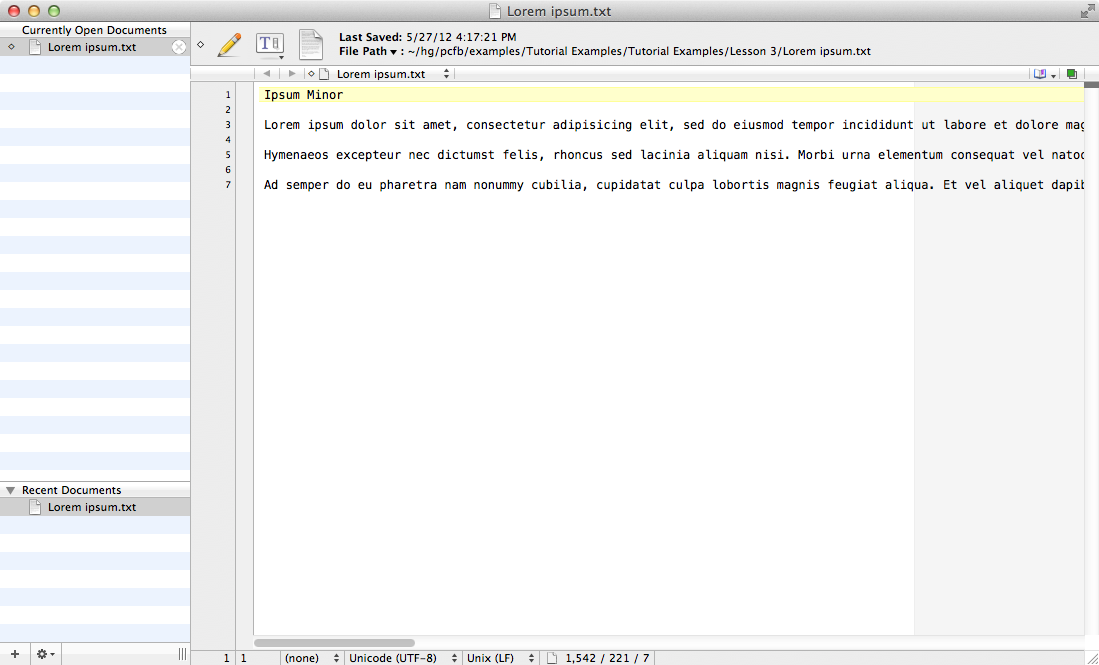

When you first open the Lorem ipsum.txt file, it looks like

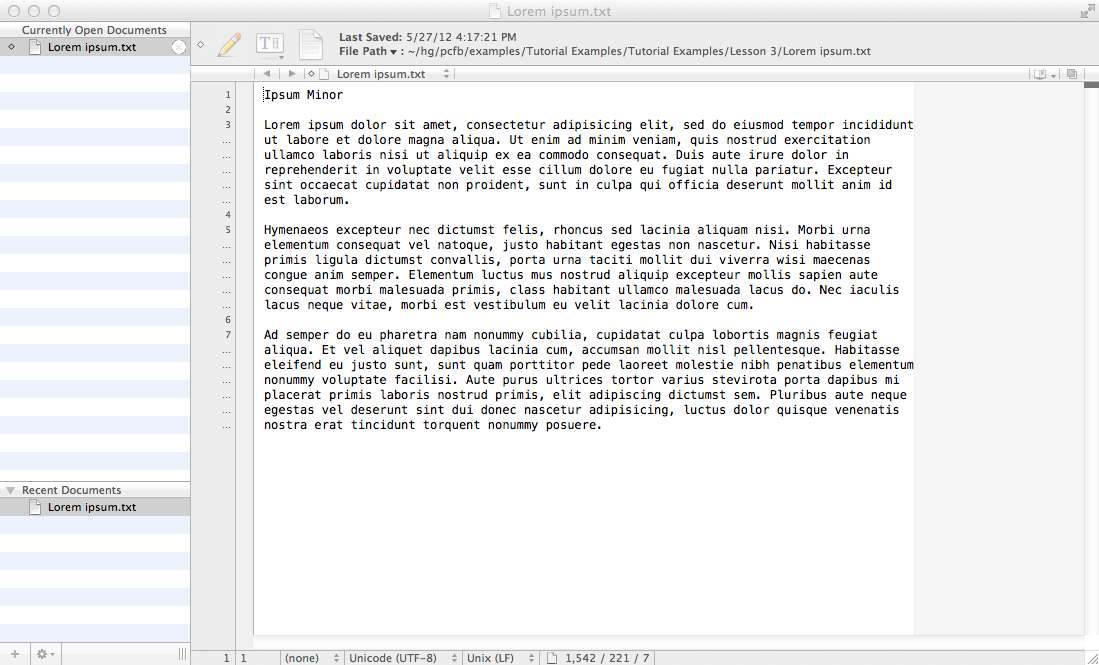

Use the TextWrangler toolbar Text Options to get here

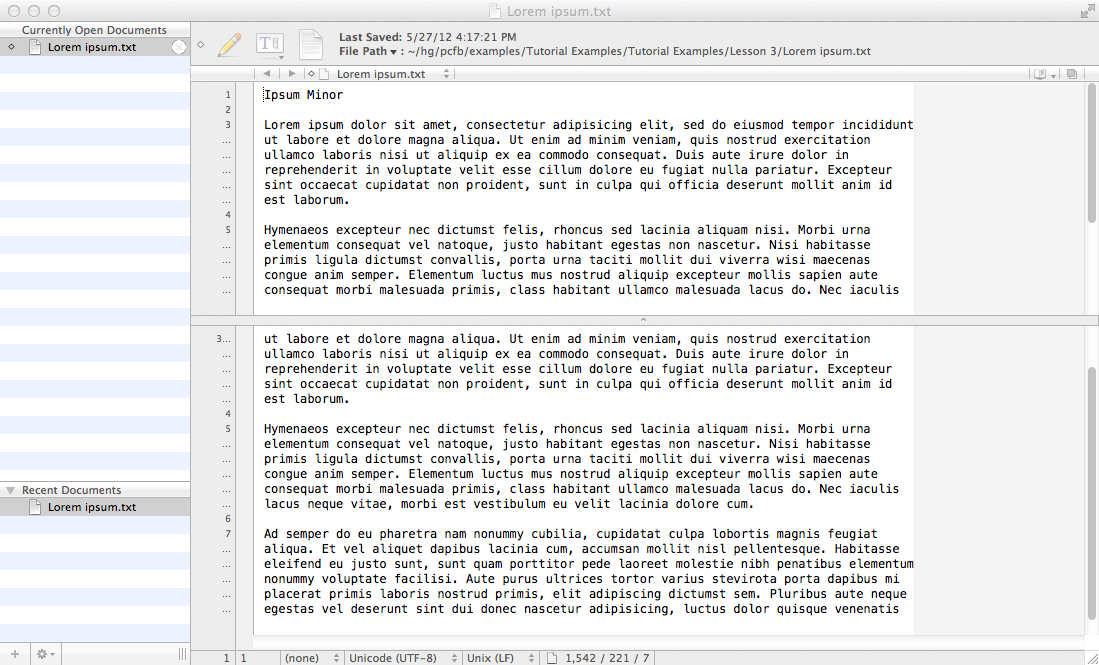

Then use the splitbar to split into two windows

Now drag the splitbar all the way to the top to get back a single window.

Finding and replacing¶

You can read all about TextWrangler in the tutorial at your leisure at home, but most things such as cut, copy and paste and undo/redo work as expected. Since we have a lot to cover, we’ll just skip ahead to lesson 7. Open the file Find and Replace Sample.txt in the Lesson 7 folder and work through the exercise on page 39.

Next, open the Email Table.txt file in the Lesson 7 folder and work through the exercise on page 42 to learn how to do search and replace on invisible characters.

Regular expressions¶

We now come to the main part of this session, which is how to use regular expressions (or regex) for text manipulation described in pages 44 to 51 of the TextWrangler tutorial. You have already come across regular expressions in the Unix session - now you will see how to use them to manipulate text files.

We’ll continue with the cats and dogs file just to get comfortable with the basic elements of regular expressions. Open the Find dialog and check the Grep and Wrap around boxes. The Grep option tells TextWrangler that we are using regular expressions, and wrap around that we want to do search and replace on the whole document regardless of where our cursor/insertion point is. If at any point you get confused over the next few paragraphs, look at the examples from page 47-49 for concrete illustrations of how to use regular expressions.

On page 45, there is a table of Wildcards. Put a period . in the Find box and click Next to see what matches. Keep clicking Next - you will see that the . matches every character as advertised. Next try \s in the Find box and click Next. What does it match? Repeat for all the Wildcards to get a good intuition of what each wildcard matches.

Now do the same with the Class patterns. Feel free to edit the text to include new words or numbers if you are curious as to how they will be matched. Also experiment with creating your own class search patterns - for example, what would a class to match DNA nucleotide symbols look like?

Now try the Repetition patterns *, *?, +, +? and ?. There is another repetition pattern {n, m} that means match at least n but not more than m of the previous character or pattern. If n is left out, we have {,m} which means match no more than m characters or patterns. If m is left out, we have {n,} which means match at least n occurrences. What is the difference between * and *? or + and +?? When would you use the greedy and non-greedy versions?

Now figure out what the ^ and $ positional assertions and the alternation patterns mean. You can use parenthesis to enclose alternations if you need to also match stuff before and/or after the alternation.

Mini-exercise¶

- Construct a regular expression to find two or more consecutive vowels in the cats and dogs file.

- Use a regular expression pattern to delete all punctuation from the example.

- Use a positional assertion with the alternation pattern to find all cat, cats, dog or dogs that occur at the end a sentence. You should find that the ends of sentences 1, 3, 5, 9 and 11 match.

Subpatterns and replace patterns¶

Regular expressions really begin to show their power when we use subpatterns and replace patterns. This can be a little tricky to wrap your head around when encountered for the first time, so we start with some simple contrived examples to give you some practice.

Subpatterns are simply any regular expression enclosed by parenthesis. For example, (.) is a subpattern that matches any character, just like . by itself. However, we can refer to captured subpatterns to refer to whatever is in the parenthesis. For example, what does the regex (.)\1 find? See if you can guess, then use TextWrangler to check if you were correct.

We can also use the captured subpatterns in the replace pattern. Here again, \1 refers to the first regex in parenthesis, 2` to the second one etc, and & to refer to the full regular expression matched (not just an individual subpattern). As an example, what does putting (.)\1([aeiou]+) in the Find box and &\2\1& do? Test it out in TextWrangler to find out what word is changed and what it is changed to.

Exercise¶

Open the file Ch3observations.txt in the examples folder. It looks like this

13 January, 1752 at 13:53 -1.414 5.781 Found in tide pools

17 March, 1961 at 03:46 14 3.6 Thirty specimens observed

1 Oct., 2002 at 18:22 36.51 -3.4221 Genome sequenced to confirm

20 July, 1863 at 12:02 1.74 133 Article in Harper's

Write a regular expression to convert it into this:

1752 Jan. 13 13 53 -1.414 5.781

1961 Mar. 17 03 46 14 3.6

2002 Oct. 1 18 22 36.51 -3.4221

1863 Jul. 20 12 02 1.74 133

Hint: Construct a regular expression to match one single line. Look at the patterns that you must capture from the original to perform the conversion. Construct the appropriate subpatterns to do so. Now construct the regular patterns between the subpatterns to match the unwanted separating characters. When you have a regular expression that matches a single line, check by clicking Next - the highlighted match should jump from one complete line to the other. Now use the references \1, \2 etc, re-ordering if necessary, and adding in filler such as extra punctuation or tabs to construct the desired replacement string. Save the regular expression by clicking the little g button on the Find dialog box and clicking Save .... Now hit Replace and see if it does what you expect. If it works, hit replace a few more times or click Replace All. If it doesn’t work, Undo and try again.

If you are totally lost and about to pull all your hair out, the construction of the solution is described in detail on pages 38-40 of the PCfB textbook. However, you should not peek at the answer without trying for at least 15 minutes.