1. 7 Lost Farms

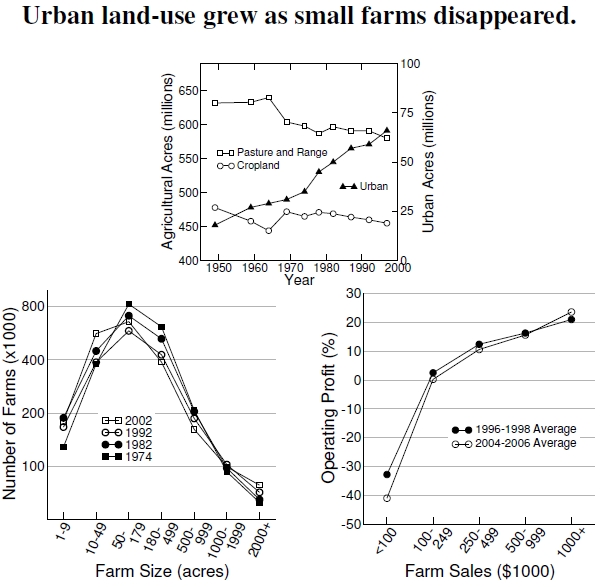

Figure 1.7: Despite a much larger human population needing food, the last half of the twentieth century in the United States saw agricultural land use decreasing by about 75 million acres while urban land use tripled, increasing by about 50 million acres (data from Lubowski et al. 2006). These land-use classifications represent about half of the United States’ 2 billion acres (excluding Alaska and Hawaii). The changing farm size distribution shows that intermediate-sized farms either break apart or merge into larger ones as small farms lose economic viability (data from MacDonald et al. 2006 and Hoppe et al. 2007).

Figure 1.7: Despite a much larger human population needing food, the last half of the twentieth century in the United States saw agricultural land use decreasing by about 75 million acres while urban land use tripled, increasing by about 50 million acres (data from Lubowski et al. 2006). These land-use classifications represent about half of the United States’ 2 billion acres (excluding Alaska and Hawaii). The changing farm size distribution shows that intermediate-sized farms either break apart or merge into larger ones as small farms lose economic viability (data from MacDonald et al. 2006 and Hoppe et al. 2007).

Are cities stealing farmland? The many classifications and changing definitions of land use complicate understanding land-use change.[31] Although the amounts of lost agricultural land roughly equal the gain in urban land, agricultural land is not being converted wholesale into suburbia because forestry land also plays an important part.[32] In any event, only a small part (3%) of the nearly 2 billion acres in the 48 states falls under the urban land-use classification, despite the impression from Figure 1.1.

The curves in Figure 1.7, however, make it clear that the United States gained people and converted land to urban use. Our urban sprawl problems likely originate from the situation underpinning the quarter-million dollar break-even value shown at the bottom right of the figure. The USDA 2002 Census compares farms between 1974 and 2002.[33] During this period the number of farms declined by 10%, from 2.3 million to 2.1 million. The average farm size remained constant at 440 acres, but that constant hides change. Intermediate-sized farms between 180 and 500 acres decreased from 616,000 to 389,000, but small farms less than 50 acres increased from 507,000 to 743,000, and 1000+ acre farms increased from 155,000 to 177,000. Presumably, medium-sized farms failed because of the break-even problem and faced either a merger into larger, economically viable farms or subdivision into hobby farms and urban development.

In the United States, our urban land tripled, agricultural land decreased slightly, and population doubled.[34] All these counterintuitive land-use changes took place because of the agricultural land’s increased efficiency through higher yields. Consider, for example, if there were 10 factories creating similar widgets and, suddenly, the productivity of each factory increased tenfold. Widgets would overun us. Even if the demand for widgets increased, say threefold, the increased supply would make the price of widgets fall. Small factories would lose money and stop production. Similarly, as agricultural yields increased over the last 60 years, small farms became unsustainable. Unlike a factory, a farm can’t produce much more than crops and still be called a farm, so farm kids take up new occupations, and the assets — land — get retooled to become subdivisions or forests.

Sadly, the farmland’s value represents the farmer’s 401(k) or 403(b) retirement plan, a source of health care money, and the only way to pay for potential nursing home care. What choice do retiring farmers have? They can’t afford to give the land to their children, and their children can’t afford to buy it from them as farmland. As farms transform into suburbs, children grow up without playing in the dirt, climbing trees, watching ants and bugs and worms, learning mechanical reasoning, and learning the delayed gratification resulting from planting a seed in the spring and eating an ear of corn in the fall (see Figure 5.10).

———————————

[31]Many categories of land exist that complicate the land-use change picture. For example, the total for wilderness-based “special use” increased from roughly 61.4 million acres in 1959 to 242.2 million acres in 2002, but much of that land (58%) is located in Alaska. All told, here’s another way to look at human population density. There are about 2.3 billion acres of land in the United States and a population of about 300 million, or about 8.7 acres per person. The 48 states (excluding Alaska and Hawaii) have 1.9 billion acres and a population of about 298 million, or about 6.4 acres per person. In contrast, the world’s population of 6.7 billion on Earth’s terrestrial surface of about 38 billion acres averages to about 5.8 acres per person across the globe.

[32]Lubowski et al. (2006) provide the land-use data through a U.S. Department of Agriculture bulletin. This bulletin shows that there are many technical issues concerning classifying land use.

[33]Two publications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, MacDonald et al. (2006) and Hoppe et al. (2007), provide great amounts of information on U.S. farms, including the farm size distribution and economic viability data I show here.

[34]I have not examined or considered the amount of foreign land that Americans rely on for agricultural production, but certainly importing food plays an important role in U.S. land-use change.

Here I state that 3% of land is urban. The 2011 Statistical Abstract of the US lists that in 2003 5.6% of US land (excluding Alaska) was “developed.” The glossary defines developed as “Large urban and built-up areas, Small built-up areas, and Rural transportation land”.