import os

import sys

import glob

import operator as op

import itertools as it

from functools import reduce, partial

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from pandas import DataFrame, Series

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_context("notebook", font_scale=1.5)

%matplotlib inline

from sympy import symbols, hessian, Function, N

Algorithms for Optimization and Root Finding for Multivariate Problems¶

Optimization/Roots in n Dimensions - First Some Calculus¶

Let’s review the theory of optimization for multivariate functions. Recall that in the single-variable case, extreme values (local extrema) occur at points where the first derivative is zero, however, the vanishing of the first derivative is not a sufficient condition for a local max or min. Generally, we apply the second derivative test to determine whether a candidate point is a max or min (sometimes it fails - if the second derivative either does not exist or is zero). In the multivariate case, the first and second derivatives are matrices. In the case of a scalar-valued function on \(\mathbb{R}^n\), the first derivative is an \(n\times 1\) vector called the gradient (denoted \(\nabla f\)). The second derivative is an \(n\times n\) matrix called the Hessian (denoted \(H\))

Just to remind you, the gradient and Hessian are given by:

One of the first things to note about the Hessian - it’s symmetric. This structure leads to some useful properties in terms of interpreting critical points.

The multivariate analog of the test for a local max or min turns out to be a statement about the gradient and the Hessian matrix. Specifically, a function \(f:\mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) has a critical point at \(x\) if \(\nabla f(x) = 0\) (where zero is the zero vector!). Furthermore, the second derivative test at a critical point is as follows:

- If \(H(x)\) is positive-definite (\(\iff\) it has all positive eigenvalues), \(f\) has a local minimum at \(x\)

- If \(H(x)\) is negative-definite (\(\iff\) it has all negative eigenvalues), \(f\) has a local maximum at \(x\)

- If \(H(x)\) has both positive and negative eigenvalues, \(f\) has a saddle point at \(x\).

Note: much of the following notes are taken from Nodecal, J., and S. J. Wright. “Numerical optimization.” (2006). It is available online via the library.¶

Convexity¶

A subset \(A\subset \mathbb{R}^n\) is convex if for any two points \(x,y\in A\), the line segment:

is also in \(A\)

A function \(f:\mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is convex if its domain \(D\) is a convex set and for any two points \(x,y\in D\), the graph of \(f\) (a subset of \(\mathbb{R}^{n+1})\) lies below the line:

i.e.

Convexity guarantees that if an optimizer converges, it converges to the global minimum.¶

Luckily, we often encounter convex problems in statistics.

Line Search Methods¶

There are essentially two classes of multivariate optimization methods. We’ll cover line search methods, but refer the reader to Nodecal and Wright for discussion of ‘trust region methods’. We should note that all of these methods require that we are ‘close’ to the minimum (maximum) we are seeking, and that ‘noisy’ functions or ill-behaved functions are beyond our scope.

A line search method is exactly as it sounds - we search on a line (in \(n\) dimensional space) and try to find a minimum. We start with an initial point, and use an iterative method:

where \(\alpha_k\) is the step size and \(p_k\) is the search direction. These are the critical choices that change the behavior of the search.

Step Size¶

Ideally, (given a choice of direction, \(p_k\)) we would want to minimize:

with respect to \(\alpha\). This is usually computationally intensive, so in practice, a sequence of \(\alpha\) candidates are generated, and then the ‘best’ is chosen according to some ‘conditions’. We won’t be going into detail regarding these. The important thing to know is that they ensure that \(f\) decreases sufficiently, according to some conditions. Interested students should see Nodecal.

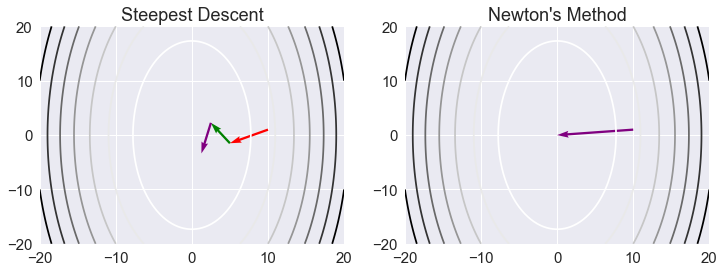

Steepest Descent¶

In steepest descent, one chooses \(p_k=\nabla f_k = \nabla f(x_k)\). It is so named, because the gradient points in the direction of steepest ascent, thus, \(-\nabla f_k\) will point in the direction of steepest descent. We’ll consider this method in its ideal case, that of a quadratic:

where \(Q\) is positive-definite and symmetric. Note that:

so the minimum occurs at \(x\) such that

Clearly, we can solve this easily, but let’s walk through the algorithm and first find the (ideal) step length:

If we differentiate this with respect to \(\alpha\) and find the zero, we obtain:

Thus,

But we know that \(\nabla f_k = Qx_k -b\), so we have a closed form solution for \(x_{k+1}\). This allows us to compute an error bound. Again, details can be found in the text, but here is the result:

where \(0<\lambda_1\leq ... \leq \lambda_n\) and \(x^*\) denotes the minimizer.

Now, if \(\lambda_1=...=\lambda_n = \lambda\), then \(Q=\lambda I\), the algorithm converges in one step. Geometrically, the contours are ellipsoids, the value of \(\frac{\lambda_n}{\lambda_1}\) elongates the axes and causes the steps to ‘zig-zag’. Because of this, convergence slows as \(\frac{\lambda_n}{\lambda_1}\) increases.

Newton’s Method¶

Newton’s method is another line-search, and here

Note that if the Hessian is not positive definite, this may not always be a descent direction.

In the neighborhood of a local minimum, the Hessian will be positive definite. Now, if \(x_0\) is ‘close enough’ to the minimizer \(x^*\), the step size \(\alpha_k =1\) gives quadratic convergence.

The advantage of multiplying the gradient by the inverse of the Hessian is that the gradient is corrected for curvature, and the new direction points toward the minimum.

#def Quad(x):

# return (x[1:])*np.sin(x[:-1])**2.0)

#def DQuad(x,y):

# return (np.array([np.cos(x)*np.sin(y)**2.0,2.0*np.sin(x)*np.cos(y)**2.0]))

def Quad(x):

return ((x[1:])**2.0 + 5*(x[:-1])**2.0)

def DQuad(x,y):

return (np.array([2.0*x,10.0*y]))

x = np.linspace(-20,20, 100)

y = np.linspace(-20,20, 100)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

Z = Quad(np.vstack([X.ravel(), Y.ravel()])).reshape((100,100))

Hinv=-np.array([[0.5,0],[0,0.1]])

plt.figure(figsize=(12,4))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.contour(X,Y,Z);

plt.title("Steepest Descent");

step=-0.25

X0 = 10.0

Y0 = 1.0

Ngrad=Hinv.dot(DQuad(X0,Y0))

sgrad = step*DQuad(X0,Y0)

plt.quiver(X0,Y0,sgrad[0],sgrad[1],color='red',angles='xy',scale_units='xy',scale=1);

X1 = X0 + sgrad[0]

Y1 = Y0 + sgrad[1]

sgrad = step*DQuad(X1,Y1)

plt.quiver(X1,Y1,sgrad[0],sgrad[1],color='green',angles='xy',scale_units='xy',scale=1);

X2 = X1 + sgrad[0]

Y2 = Y1 + sgrad[1]

sgrad = step*DQuad(X2,Y2)

plt.quiver(X2,Y2,sgrad[0],sgrad[1],color='purple',angles='xy',scale_units='xy',scale=1);

plt.subplot(122)

plt.contour(X,Y,Z);

plt.title("Newton's Method")

plt.quiver(X0,Y0,Ngrad[0],Ngrad[1],color='purple',angles='xy',scale_units='xy',scale=1);

#Compute Hessian and plot again.

Coordinate Descent¶

Another method is called ‘coordinate’ descent, and it involves searching along coordinate directions (cyclically), i.e.:

where \(m\) is the number of steps.

The main advantage is that \(\nabla f\) is not required. It can behave reasonably well, if coordinates are not tightly coupled.

Newton CG Algorithm¶

Features:

- Minimizes a ‘true’ quadratic on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) in \(n\) steps

- Does NOT require storage or inversion of an \(n \times n\) matrix.

We begin with \(:\mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). Take a quadratic approximation to \(f\):

Note that in the neighborhood of a minimum, \(H\) will be positive-definite (and symmetric). (If we are maximizing, just consider \(-H\)).

This reduces the optimization problem to finding the zeros of

This is a linear problem, which is nice. The dimension \(n\) may be very large - which is not so nice.

General Inner Product¶

Recall the axiomatic definition of an inner product \(<,>_A\):

For any two vectors \(v,w\) we have

\[<v,w>_A = <w,v>_A\]For any vector \(v\)

\[<v,v>_A \;\geq 0\]with equality \(\iff\) \(v=0\).

For \(c\in\mathbb{R}\) and \(u,v,w\in\mathbb{R}^n\), we have

\[<cv+w,u> = c<v,u> + <w,u>\]

These properties are known as symmetric, positive definite and bilinear, respectively.

Fact: If we denote the standard inner product on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) as \(<,>\) (this is the ‘dot product’), any symmetric, positive definite \(n\times n\) matrix \(A\) defines an inner product on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) via:

Just as with the standard inner product, general inner products define for us a notion of ‘orthogonality’. Recall that with respect to the standard product, 2 vectors are orthogonal if their product vanishes. The same applies to \(<,>_A\):

means that \(v\) and \(w\) are orthogonal under the inner product induced by \(A\). Equivalently, if \(v,w\) are orthogonal under \(A\), we have:

This is also called conjugate (thus the name of the method).

Conjugate Vectors¶

Suppose we have a set of \(n\) vectors \(p_1,...,p_n\) that are mutually conjugate. These vectors form a basis of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Getting back to the problem at hand, this means that our solution vector \(x\) to the linear problem may be written as follows:

So, finding \(x\) reduces to finding a conjugate basis and the coefficients for \(x\) in that basis.

If we let \(A=H\),note that:

and because \(x = \sum\limits_{i=1}^n \alpha_i p_i\), we have:

we can solve for \(\alpha_k\):

Now, all we need are the \(p_k\)‘s.

A nice initial guess would be the gradient at some initial point \(x_1\). So, we set \(p_1 = \nabla f(x_1)\). Then set:

This should look familiar. In fact, it is gradient descent. For \(p_2\), we want \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) to be conjugate (under \(A\)). That just means orthogonal under the inner product induced by \(A\). We set

I.e. We take the gradient at \(x_1\) and subtract its projection onto \(p_1\). This is the same as Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization.

The \(k^{th}\) conjugate vector is:

The ‘trick’ is that in general, we do not need all \(n\) conjugate vectors. In fact, it turns out that \(\nabla f(x_k) = b-Ax_k\) is conjugate to all the \(p_i\) for \(i=1,...,k-2\). Therefore, we need only the last term in the sum.

Convergence rate is dependent on sparsity and condition number of \(A\). Worst case is \(n^2\).

BFGS - Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno¶

BFGS is a ‘quasi’ Newton method of optimization. Such methods are variants of the Newton method, where the Hessian \(H\) is replaced by some approximation. We we wish to solve the equation:

for \(p_k\). This gives our search direction, and the next candidate point is given by:

.

where \(\alpha_k\) is a step size.

At each step, we require that the new approximate \(H\) meets the secant condition:

There is a unique, rank one update that satisfies the above:

where

and

Note that the update does NOT preserve positive definiteness if \(c_k<0\). In this case, there are several options for the rank one correction, but we will not address them here. Instead, we will describe the BFGS method, which almost always guarantees a positive-definite correction. Specifically:

where we have introduced the shorthand:

If we set:

we satisfy the secant condition.

Nelder-Mead Simplex¶

While Newton’s method is considered a ‘second order method’ (requires the second derivative), and quasi-Newton methods are first order (require only first derivatives), Nelder-Mead is a zero-order method. I.e. NM requires only the function itself - no derivatives.

For \(f:\mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), the algorithm computes the values of the function on a simplex of dimension \(n\), constructed from \(n+1\) vertices. For a univariate function, the simplex is a line segment. In two dimensions, the simplex is a triangle, in 3D, a tetrahedral solid, and so on.

The algorithm begins with \(n+1\) starting points and then the follwing steps are repeated until convergence:

Compute the function at each of the points

Sort the function values so that

\[f(x_1)\leq ...\leq f(x_{n+1})\]Compute the centroid \(x_c\) of the n-dimensional region defined by \(x_1,...,x_n\)

Reflect \(x_{n+1}\) about the centroid to get \(x_r\)

\[x_r = x_c + \alpha (x_c - x_{n+1})\]Create a new simplex according to the following rules:

If \(f(x_1)\leq f(x_r) < f(x_n)\), replace \(x_{n+1}\) with \(x_r\)

If \(f(x_r)<f(x_1)\), expand the simplex through \(x_r\):

\[x_e = x_c + \gamma (x_c - x_{n+1})\]If \(f(x_e)<f(x_r)\), replace \(x_{n+1}\) with \(x_e\), otherwise, replace \(x_{n+1}\) with \(x_r\)

If \(f({x}_{r}) \geq f({x}_{n})\), compute \(x_p = x_c + \rho(x_c - x_{n+1})\). If \(f({x}_{p}) < f({x}_{n+1})\), replace \(x_{n+1}\) with \(x_p\)

If all else fails, replace all points except \(x_1\) according to

\[x_i = {x}_{1} + \sigma({x}_{i} - {x}_{1})\]

The default values of \(\alpha, \gamma,\rho\) and \(\sigma\) in scipy are not listed in the documentation, nor are they inputs to the function.

Powell’s Method¶

Powell’s method is another derivative-free optimization method that is similar to conjugate-gradient. The algorithm steps are as follows:

Begin with a point \(p_0\) (an initial guess) and a set of vectors \(\xi_1,...,\xi_n\), initially the standard basis of \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

- Compute for \(i=1,...,n\), find \(\lambda_i\) that minimizes \(f(p_{i-1} +\lambda_i \xi_i)\) and set \(p_i = p_{i-1} + \lambda_i\xi_i\)

- For \(i=1,...,n-1\), replace \(\xi_{i}\) with \(\xi_{i+1}\) and then replace \(\xi_n\) with \(p_n - p_0\)

- Choose \(\lambda\) so that \(f(p_0 + \lambda(p_n-p_0)\) is minimum and replace \(p_0\) with \(p_0 + \lambda(p_n-p_0)\)

Essentially, the algorithm performs line searches and tries to find fruitful directions to search.

Solvers¶

Levenberg-Marquardt (Damped Least Squares)¶

Recall the least squares problem:

Given a set of data points \((x_i, y_i)\) where \(x_i\)‘s are independent variables (in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) and the \(y_i\)‘s are response variables (in \(\mathbb{R}\)), find the parameter values of \(\beta\) for the model \(f(x;\beta)\) so that

is minimized.

If we were to use Newton’s method, our update step would look like:

Gradient descent, on the other hand, would yield:

Levenberg-Marquardt adaptively switches between Newton’s method and gradient descent.

When \(\lambda\) is small, the update is essentially Newton-Gauss, while for \(\lambda\) large, the update is gradient descent.

Newton-Krylov¶

The notion of a Krylov space comes from the Cayley-Hamilton theorem (CH). CH states that a matrix \(A\) satisfies its characteristic polynomial. A direct corollary is that \(A^{-1}\) may be written as a linear combination of powers of the matrix (where the highest power is \(n-1\)).

The Krylov space of order \(r\) generated by an \(n\times n\) matrix \(A\) and an \(n\)-dimensional vector \(b\) is given by:

These are actually the subspaces spanned by the conjugate vectors we mentioned in Newton-CG, so, technically speaking, Newton-CG is a Krylov method.

Now, the scipy.optimize newton-krylov solver is what is known as a ‘Jacobian Free Newton Krylov’. It is a very efficient algorithm for solving large \(n\times n\) non-linear systems. We won’t go into detail of the algorithm’s steps, as this is really more applicable to problems in physics and non-linear dynamics.

GLM Estimation and IRLS¶

Recall generalized linear models are models with the following components:

A linear predictor \(\eta = X\beta\)

A response variable with distribution in the exponential family

An invertible ‘link’ function \(g\) such that

\[E(Y) = \mu = g^{-1}(\eta)\]

We may write the log-likelihood:

where \(\eta_i = \eta(x_i,\beta)\).

Differentiating, we obtain:

Written slightly differently than we have in the previous sections, the Newton update to find \(\beta\) would be:

Now, if we compute:

Taking expected values on the right hand side and noting:

and

So if we replace the Hessian in Newton’s method with its expected value, we obtain:

Now, these actually have the form of the normal equations for a weighted least squares problem.

\(A\) is a weight matrix, and changes with iteration - thus this technique is iteratively reweighted least squares.

Constrained Optimization and Lagrange Multipliers¶

Often, we want to optimize a function subject to a constraint or multiple constraints. The most common analytical technique for this is called ‘Lagrange multipliers’. The theory is based on the following:

If we wish to optimize a function \(f(x,y)\) subject to the constraint \(g(x,y)=c\), we are really looking for points at which the gradient of \(f\) and the gradient of \(g\) are in the same direction. This amounts to:

(often, this is written with a (-) sign in front of \(\lambda\)). The 2-d problem above defines two equations in three unknowns. The original constraint, \(g(x,y)=c\) yields a third equation. Additional constraints are handled by finding:

Lagrange Multipliers

The generalization to functions on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) is also trivial: