6.10 Baltimore: Vegetation, Wealth, & Education

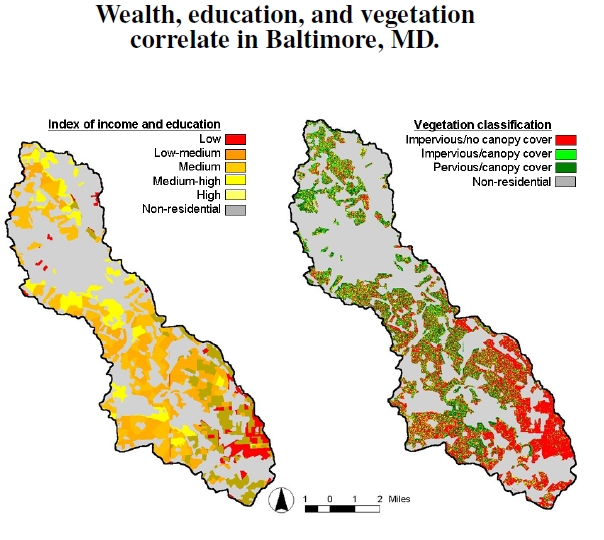

Figure 6.10: Visual correlation between vegetation and a combined measure of income and education in Baltimore, Maryland (courtesy of M. Grove, after Grove and Burch 1997). Darker areas represent lower income/education and lower levels of vegetation.

Figure 6.10: Visual correlation between vegetation and a combined measure of income and education in Baltimore, Maryland (courtesy of M. Grove, after Grove and Burch 1997). Darker areas represent lower income/education and lower levels of vegetation.

Another example connecting vegetation with socioeconomic factors comes from Baltimore, Maryland (see Figure 6.10). These plots show the correlation between lots of vegetation and high income and education.Conversely, low-income areas with low levels of education tend to have low levels of vegetation.[36] Recent research on Baltimore’s distribution of vegetation finds that population density and socioeconomic status, though important, incompletely predict variations in landcover. According to more recent, refined studies, understanding the connections involved in urban correlations with vegetation extend beyond taking a snapshot of a city: In Baltimore, for example, vegetative cover in the 1990s had a better connection to socioeconomic status in 1970 than it did to socioeconomic status in 1990! In other words, like the time lag between heat and mortality (Figure 6.1), the landscaping decisions made by residents 20 years ago affect vegetation patterns today more than the people who live there now.

Yet, vegetation distributions involve socioeconomic factors. Lifestyle behavior and characteristics, household lifestage, and median housing age are all important. Lifestyle behavior — a term arising from analyzing and categorizing census data — includes the social pressure to meet community expectations concerning landscaping. Household lifestage and lifestyle characteristics include such details as family composition, type of housing one lives in, and how long the members of the household have been together. Housing age also connects to vegetation status: In Durham’s newest subdivisions, developers bulldoze trees (not to mention all the associated animal kingdoms) to simplify the house-building process. Thus, at house age zero there are no trees, except for the small planted ones, and certainly no frogs or salamanders. Vegetation levels can only increase!

Positive signs exist, though. In Baltimore, socioeconomic status didn’t predict public provisioning of vegetation in public right-of-ways—those spaces between streets and sidewalks, parks, and other spaces under urban foresters’ purview. Baltimore invokes fair practices across income and social levels, at least in this respect. However, concerning private residential vegetation, social stratification best predicted the space available for vegetation — parcel area minus house area — while lifestyle behavior best predicted whether that space has vegetation. Disproportionate rentership, tied to low education and low-income areas, likely explains the correlation’s source: Tenants have little motivation to landscape their landlord’s property.

————————————–

[36]Grove and Burch (1997) studied vegetation and socioeconomic variables in Baltimore, Maryland. This work has been extended and updated by Grove et al. (2006) and Troy et al. (2007).